The captain of the Canadian ship “Ohio”, Rupert A. Ryan, was 27 years old and a newlywed. His bride was on her first voyage at sea. The captain of the American schooner Theodore Roosevelt, James McHenry, lived on Shepherd Street in Gloucester.

The Saint John built brigantine, owned in NY, carrying timber from Nova Scotia, was caught in and battled through a blizzard without success Jan 3-6, 1905 after surmounting a series of gales since Dec. 26.

The terrifying and triumphant tale made global news. Here’s the coverage–great reads–published in the Boston Globe and Nova Scotia papers, a worthy inspiration for a film or series set here in Gloucester.

After reading through the stories, drive past the house on Shepherd St. today. It’s easy to think about the meal that night, the wife and children waiting for weeks at home and worried as the return deadline came and went, the Gloucester crew willing to take to the dories in rough waters to aid the Ohio despite risks and past losses, the generous hosting of the young newlywed storm survivors, and the local hospital care the N.B. crew received come morning, including “three Scandinavians and 1 Spaniard” unnamed.

Boston Globe

“GLOUCESTER – Five persons rowed up the harbor in a dory from Eastern point through the snow at 8 o’clock tonight and landed on the Atlantic docks.

They were Capt. James McHenry and two of his crew of the schooner Theodore Roosevelt of this port, and Capt. and Mrs. Rupert A. Ryan of the brigantine Ohio of St. John, New Brunswick (NB).

The Roosevelt had anchored in the roadstead until morning. About four miles astern with a prize crew of eight of the Roosevelt’s crew aboard, lies the Ohio.

The members of crew of the Ohio, badly frostbitten, are aboard the Roosevelt. Tomorrow they will be brought to the hospital.

The Ohio left Kingsport, NS, December 26, with a cargo of lumber, deals and laths in the hold and on deck, comprising about 320,000 feet of lumber.

Disaster Off Grand Manan.

Capt. Ryan is 27, and has been at sea almost since he was able to walk. He says he never experienced anything like the recent storm for severity. The entire passage of the Ohio was a series of gales and extreme cold.

She was obliged to lie at Spencer harbor, NS, a week, and left there Jan. 3, with the wind east-northeast.

Tuesday morning while off Grand Manan, in the bay of Fundy, a northeast snowstorm and gale broke on them in all its fury, and from then until Wednesday morning the vessel was practically at the mercy of the wind and sea.

The sails of the Ohio were carried away. Huge seas broke aboard, submerging everything on deck, filling the cabin and forecastle, and carrying away part of the deck load.

To add to the terrors of the storm the Ohio sprang a leak, and although the water rose high in the hold, the fact that she was lumber-laden prevented her from sinking.

It was bitter cold, and the men at the pumps were chilled to the bone, being drenched again and again by the icy seas.

The skylight was lifted, and Mrs. Ryan, who is a young woman of slight build, about 24, was forced to retreat to the top berth of her stateroom to escape the water.

Crew Works to Exhaustion.

Wednesday and Thursday the seas broke over the vessel constantly. The wheel and compass binnacle was carried away and the vessel wallowed all but helpless. The water and spray froze as it struck and coated the deckload with a heavy mass of ice, dragging the bow of the vessel’s head nearly two feet under.

From Wednesday morning until Thursday morning at 8 neither food, drink, nor shelter was available to the crew exposed to the icy cold, and at that time the crew gave up exhausted

Human nature could stand no more. Every man from the mate down fell to the deck clinging to mast or rigging to prevent being swept overboard. Only Capt. Ryan was able to get about. All, including the captain, were badly frostbitten.

Early Thursday morning Capt. Ryan had hoisted a signal of distress in the rigging.

Captain’s Wife First Rescued.

The schooner Theodore Roosevelt of this port was coming home from a six week’s voyage to the Grand banks, where she had been on a halibut voyage, when she sighted the Ohio. She was soon alongside. Dories were put over in quick order. The woman was first taken aboard and the others, more dead than alive, quickly followed.

The poor fellows were in pitiable condition. Food, warm drink, and dry clothing were given them, and their frostbitten hands, feet and faces were bathed and everything possible done for them.

Eight men of the Roosevelt crew, Sylvester Thompson, David Higgin, Neal McPhee, Michael White, James de Loucrie, Angus MacDonald, Lafayette Johnson and Gardner Sullivan, the latter a state of Maine man, were put aboard as a prize crew. A steering wheel was improvised and jury sails set.

The Roosevelt showed the way for Gloucester and the brigantine followed, each burning lights at night.

Safe Around Eastern Point.

Just after 7 tonight the Roosevelt rounded Eastern point and anchored. Just prior to that the prize crew had signaled from Thatchers with lights.

Besides Capt. Ryan and wife, the Ohio’s crew comprised, first mate Enos Barshure of Kingsport, N.S., second mate Harry burns, steward Howard Neanes of Loringsville, N.S., and four men of various nationalities before the mast.

The Ohio is about 25 years old, 325 tons and was built at St. John, NB her present hailing port. Vessel and cargo are owned by Scanlan Bros of New York, where she was bound.

While all the Ohio’s men are badly off, the mate, Barsure fared the worst. Capt. Ryan’s face and hands are also badly affected.

Capt. and Mrs. Ryan were the guests of Capt. McHenry on Shepherd St tonight.

Capt. McHenry’s homecoming was especially welcome as his wife and three little children were worrying concerning his absence in the heavy storms.”

Author unknown. Boston Globe, January 1905

Published in CanaDA

“Gloucester, Mass. Jan. 6 – The fishing sch. Theodore Roosevelt of this port which anchored inside the breakwater tonight, had on board nine happy passengers, comprising Captain Rupert A. Ryan, Mrs. Ryan, and seven sailors, all of whom were rescued from the British brigantine Ohio yesterday off Grand Manan. The Ohio was leaking badly and had suffered the loss of sails and received other severe damage during the terrible gales of the past three days. The Roosevelt put a prize crew on board the Ohio and kept company with her until this evening when five miles off Thatcher’s island. The former then left her prize behind and proceeded to this port as rapidly as possible, leaving the prize crew to work the unfortunate vessel into port. With the present favorable winds it is believed this will be done during the night.

The Ohio left Kingsport, N.S., for New York Dec. 26, with a cargo of 320,000 feet of lumber, and after a series of gales, made Spencer Island, N.S. for a harbor, sailing from there on Jan. 3. Hardly had they put to se when the wind came up strong from the northeast, the weather became terribly cold, followed by a blinding snow storm off Grand Manan, the vessel caught the full force of the gale, the seas constantly breaking over her. On Wednesday morning a big wave swept over the vessel, carrying away a portion of her deckload, her binnacles and smashing the wheel. This rendered it impossible to steer the vessel and, tossed at the mercy of the sea, she began to leak. All hands were called to the pumps, but the cold was so intense that the crew were frost-bitten and were soon forced to stop work.

Another sea smashed the skylights, filling the cabin with water. Mrs. Ryan was forced to take refuge in the upper bunk to escape drowning.

The heavy seas not only flooded the vessel, but they also spoiled the ship’s food and fresh water supply, while the vessel itself became a mass of ice from stem to stem.

With no fire, their food and water supply gone, the weather freezing cold and a raging storm in progress, the sufferings of those on the Ohio were terrible all though Wednesday night.

About 8 o’clock Thursday morning the weather having moderated considerably, a sail was sighted and a signal of distress was raised by the half-frozen men on the Ohio and this was seen by the sch. Roosevelt, which was returning from a Grand Banks fishing trip. The Roosevelt quickly bore down upon her and learning that the crew desired to be taken off, at once began preparations for their rescue. Captain James McHenry of the Roosevelt called for volunteers and every one of the eighteen members of the crew responded.

A heavy sea was running, which made the attempted rescue a most perilous undertaking. Two dories, each containing two men, were sent off to the Ohio, and after much difficulty the life-savers succeeded in taking off the nine persons on the Ohio.

All were badly frost bitten, half frozen and half starved, but when once aboard the Roosevelt they were furnished with dry clothing and food and drink, and given every possible assistance by their rescuers.

After consultation with his own men, Captain McHenry decided to put a prize crew of eight men on the Ohio and endeavor if possible to work her into Gloucester harbor.

This, it is believed, can be done, as her cargo of lumber serves to keep her afloat, and the wind tonight is favorable for the undertaking.

Upon the arrival of the Roosevelt in port, she anchored inside the breakwater, and Captain and Mrs. Ryan came to the city as guests of Captain McHenry. The crew remained on board the Roosevelt for the night. The names of those comprising the Ohio’s crew are: Enos Barkshire, first mate. Harry Barrows, second mate. Howard Naves, steward. Three Scandinavians and one Spaniard whose names are unknown.

Mrs. Ryan, who is but 24 years of age, and who has been married but a short time, was taking her first trip at sea with her husband.

The Ohio is a vessel of 325 tons, hails from St. John N.B. and is owned by Scanlon Bros. of New York.

—

The Ohio was built by Andrew Ruddock in his yard on the Strait Shore in 1882 to the order of Charles A. Palmer. She was 130 feet long, 29 feet beam and 14 feet depth of hold, tonnage 348.”*

1905- Terrible Experience of a St. John Brigantine. Capt. Ryan, His Wife and Crew Taken from Storm Tossed Ohio by American Fishing Schooner, Daily Sun. *Editor added beneath Gloucester wired story. Surmising because it mentioned that the brigantine was British.

wires in Perth, NJ and St. Paul, MN

1913

In 1913, the reverse would happen. The Theodore Roosevelt wrecked on Nova Scotia rocks, “12 miles west of Point Prim Light”, a total loss of vessel and freight. The Canadian “little river tug Sissiboo” set out to help.

1902

In 1902, three years prior to the heroic rescue almost to the day, Capt. McHenry relayed the sad news that the Theodore Roosevelt lost two men, trawling in a dory was emphasized:

“Halifax, N.S., Dec. 30– The loss by drowning of two men from the Gloucester fishing schooner Theodore Roosevelt is reported by the Gloucester schooner Annie Greenlaw, Capt. Crowell, which put in here last night to land a sick man, Daniel McEachern. The Greenlaw on Dec. 26, at Bank Quero. spoke the Theodore Roosevelt, and Capt. McHenry of the latter vessel reported that William Johnson and Joseph Brennan were drowned, a heavy sea upsetting their dory while they were tending their trawls.

The loss of Roosevelt’s two men was reported by wire to the schooner’s owners, in Gloucester, last night, but it was understood in that city that the men had strayed while tending trawls, not that they were drowned.”

Dec. 30, 1902

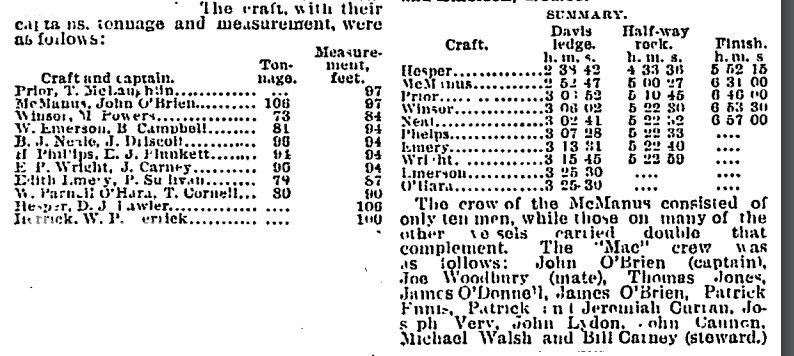

| THEODORE ROOSEVELT | OHIO |

| American schooner | Canadian brigantine |

| fishing and cargo transport | cargo transport |

| built in 1901in Gloucester | built in 1882* by Andrew Ruddock in his Strait Shore St. John NB ship yard for Charles A. Palmer *An 1847 brigantine “Ohio” built at Marietta, OH was involved in the illegal slave trade |

| 90 tons | 325 tons | 348 tonnage |

| 125 feet wood hull | 130 feet long 29 feet beam 12 feet depth of hold |

| wrecked Oct 31, 1913 | wrecked Jan 4-6, 1905 |

| then owned by | then owned by Scanlan Bros., NY |

![DORYRACEBANNER [640x480] DORYRACEBANNER [640x480]](https://goodmorninggloucester.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/doryracebanner-640x480.jpg)