Gloucester, Ma. January, 2022.– Reading about the potential ‘Big Snow’ forecast for the upcoming weekend prompted me to re-read one of my favorite winter articles. Back in January 1890, Boston Globe regional journalists interviewed some 100 New Englanders who had each faced down 80 or 90 winters, and shared heartwarming vignettes from these extraordinary people. Whether a farmer, teacher, historian, geologist, notable townie, banker, ice man, fisherman pilot, driver,– all remained active and impressive. A few were still working.

This week I put the same questions to my mother-in-law, who braced Montana and Minnesota storms, and my husband. I was as delighted and impressed by their stories as I was by those profiled in this classic piece. Try it! Hopefully you’ll share what you hear or recall as well.

But first, settle in for an

1890 Boston Globe. Great Read.

May their (uncredited) journalism inspire many winter days. I wonder if Tom Herbert was one of the writers. (The Plymouth report includes a Gloucester mention.)

“Bare-footed winters” was a popular description then, and a new term for me. One account provided context of their unique present life circumstance (battling the storm while the Russian flu* (1889-1892) raged). None mentioned the recent “Great Blizzard” back in March of 1888.

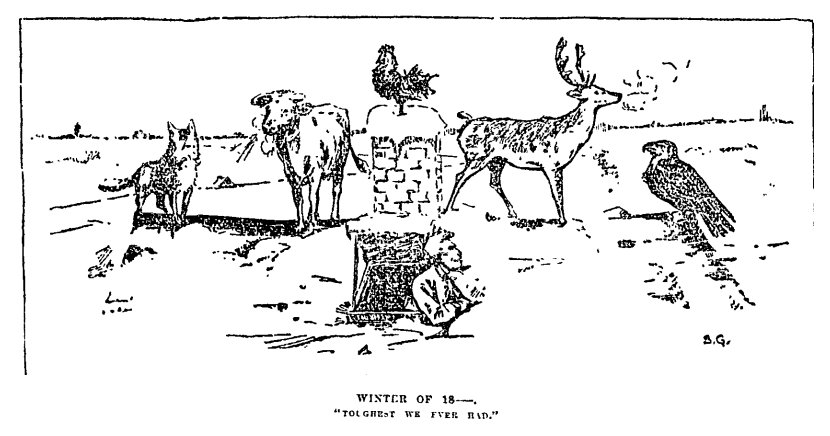

photo description: Apt pair of illustrations accompany the Boston Globe 1890 article, author(s) and artist(s) unidentified

What weather!

Did you ever see the like?

Where has the New England winter gone?

What is the matter?

These are the familiar questions of the day.

Everybody talks about the weather and particularly the fickle weather of the present. The Sunday Globe has asked these questions of the oldest inhabitants in more than 30 New England communities, and the reminiscences called up thereby are graphic pictures of the old-time winter, when “Everything went on runners at Thanksgiving and didn’t come off till Fast day.”

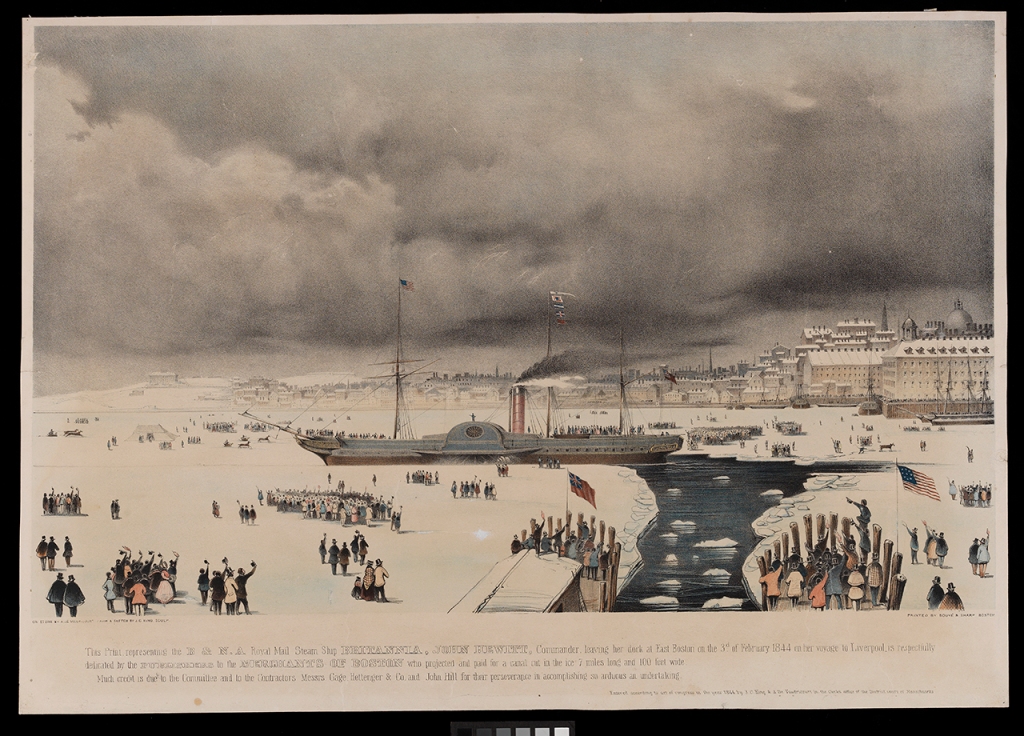

Here in Boston the hard winters found their climax in February 1844 when the British steamer RMS Britannia needed to cut out of the Harbor, which was entirely frozen over. (author. note- scroll down beneath illustration to see illustration)

All the old and middle-aged people of this neighborhood invariably begin with that unusual condition of affairs when they discuss the weather of the past. But the harbor has since been frozen over again. In January 1857, the merchants organized a crew, who chopped a channel out of the harbor ice seven miles in length. In that month the thermometer went 16 degrees below zero, and it did not rise above zero for two weeks. Only once before in the record of the town has the thermometer gone lower: it fell to 20 in December 1790.

FROZEN WAY OUT TO SEA. How one winter struck Billy Patterson- Chatham big storms.

Chatham, Jan. 18 – “Uncle Bill Patterson.” Over 80 years old, who has battled with the wild ocean nearly 70 winters in various parts of the world, says:

“The toughest winter I can remember was in the early forties when one February everything was frozen solid not only from out her away up to Gay Head, but outside of Nantucket it froze way southward into the Atlantic that we could not see beyond the range of ice from the royal trucks of a ship aboard which I was pilot. The ice had caught her some distance southward, and heavy gales forced her towards the land. We had both anchors down to keep from going ashore where the ice cakes had piled up shelvingly to over 60 feet high and meant death to us if we didn’t keep cutting the ice away from our chains so the ship could ride to them and prevent going ashore. All this was outside, remember, not in the sound, and we could see ocean steamers bound ‘across’ from New York and they often had to make a long detour southward to clear the ice. We lay there a week before we got out of it, and when we finally reached Holmes Hole we found vessels which had been frozen in there four weeks.

“Another tough winter was I think, in 1832, when the brig Sultana came in the south channel in a terrific easterly snowstorm and fetched up on the beach here. It froze so hard we carted her whole cargo right across the harbor. That brig’s captain had sworn that ‘By G-d, I’ll weather Cape Cod tonight, blow high or low,’ but he didn’t do it. The mildest winter I ever saw was last winter (1889), and as regards this winter—well, I don’t see as we’re goin’ to have any.”

The toughest winter that “Sam” Nickerson, the veteran stage driver, can remember was about 1855 when the snow was so deep there were many places along the railroad track where one could walk along with the telegraph wires not over knee high, and the railroad tracks had to be dug out by hand shoveling all the way out from Boston. Stage drivers and sailors suffered in those days.

MARRIED AND SNOWED IN. A Centenarian Tells of A Mishap to Her Great Grandfather

Hyde Park, Jan. 18—Mrs. Matilda Whiting Vose, 102 years old, and probably the oldest person living within a radius of a good many miles of Boston, was seen the other day by your correspondent, who asked her several questions regarding the winters of today as compared with those of a century ago.

Mrs. Vose, while in extremely good health for one so old, was unable to trace the weather back through the labyrinth of years past, her memory not being as acute as it was a year or two ago, but she gave it as her opinion that the present winter is the mildest of any she ever remembered. Two hundred years ago New England weather was far different from nowadays. Her great-grandfather Jeremiah Whiting, who then lived at Greenledge, Dedham, started for West Roxbury, only a short distance away to get married. The snow when he started was so deep that he had to travel the entire distance on showshoes. He succeeded in getting there and being married, but was literally snowed in as the fast-falling snow piled up so high that he and his fair bride were prisoners in the homestead for six weeks.

A century ago it was no uncommon sight to see children coasting from second story windows over the frozen surface and some 40 or 50 years ago the snow was so deep in this region that the roads had to be dug out before the stages could go into Boston; and when this was accomplished it was like riding through a tunnel, the snow being piled on either side higher than the top of the stage. In the early days of the Boston, Hartford & Erie road the snow as so deep on several occasions that business men who had gone into Boston in the morning were unable to return at night, but instead fell to with a wall and helped the railroad men cut a passage through the snow which was piled up almost as high as the roofs of the coaches in the cuts, a job which lasted them all night.

BANGOR’S ORACLE. A Genuine Oldest Inhabitant on Two Remarkable Years.

Bangor, ME., Jan. 18—When any statement is made in Bangor concerning the “oldest inhabitant,” it means something, for the individual who answers to that description here is Ira Chamberlain, who, at the age of 97 years, has a mind phenomenal for its brightness, and is never deterred from taking his daily walk by the severest kind of weather. His memory is very clear, and he can tell about the weather way back to past generations.

The mildest winter in his recollection was that of 1830-31, when through December the average height of the mercury was 60. On New Year’s day farmers around Bangor were ploughing in their fields while there was navigation in the river until Jan. 9 and schooners plied between Bangor and the down-river points, as in the summer. There was no snow to make sleighing until March, and then it came in great quantities and melted so quickly that a damaging freshet was produced.

He remembers two equally cold winters. The first was in 1812, when the temperature was intensely frigid for four months, and the month of February was the coldest known in the history of New England. It was that winter that he saw the bay at Damariscotta frozen over, even the salt water yielding to the remarkably low temperatures. The next winter was in 1852-53 when the Penobscot river closed in November, five weeks earlier than usual, and imprisoned a dozen or more vessels in the harbor of Bangor. This was the time that crews of men armed with saws, were placed at work, the vessels freed, and then a channel was sawed for them from the harbor down the river to open water. This incident, it is asserted, is recalled by many of the present citizens of Bangor. Mr. Chamberlain says that, with the exception of 1831-32, which he mentioned, this (1889-1890) is by far the mildest winter that he has known.

PLAYED BALL TILL MARCH. Capt. Benjamin F. Swett of Portland on One Queer Winter.

Portland, Jan. 18.—Although Capt. Benjamin F. Sweet isn’t the “oldest inhabitant,” he is getting well up with that individual in point of years, and when a man can remember back 75 years distinctly and can recall with vividness the events of that period, he is certainly old enough for present purposes. It is a matter of doubt who is now the actual “oldest inhabitant” of Portland, but the captain is one of the oldest men here, and his memory of past events is exceeded only by his interest in the present. Said he:

“The mildest winter in my recollection was that of 1819-20. The boys played ball all winter up to March. Then the snow came down in good earnest, and it was all folks wanted to do to break out the roads. That kept everybody busy through March. The winter of 1830-31 was also extremely mild, but the mildest winter in my recollection, and the mildest for the past 75 years, was, as I have said that of 1819-20.

“The coldest winter in my recollection was that of 1831-32. It was very cold all winter. I remember that I helped the father of Gov. Selden Connor build a mill at Oldtown that winter.”

A number of other old people recall the winter of 1819-20 as having been remarkably mild, and some say the same of the winter of 1818.

WHAT AN ICE MAN REMEMBERS. F.C. Bryant of Biddeford says the climate is changing

Biddeford, Jan. 18- Foxwell C. Bryant, the veteran who will be 93 years old in April, has been talking about the weather. In spite of his advanced age Mr. Bryant’s faculties are practically unmarred and his memory is remarkable. His half-century’s experience in the ice business renders him authority upon the weather, and if the old gentleman has a pronounced weakness it is the indulgence in reminiscence upon that topic.

He says this winter is the mildest, with the exception of the last, of any of the 92 through which he has lived. He thinks last winter even milder, and says that upon the 18th of last January, he ploughed in his field without finding a sign of frost in the ground. In his younger days he always reckoned upon the river freezing over by Dec. 1 and he remembered that one year, he thought it was 1827, it closed up Nov. 5, and did not open until late March. That winter was one of steady and extreme cold, and one Friday in January became historic as “Cold Friday.” The following winter of 1828, he remembered as the mildest of his life with the exception of the two last. There had been very little snow or cold until the latter part of January, when there came a snap which froze the ice to a thickness of 16 inches. The “snap” was of brief duration, however, and February brought such warm weather that on the 22nd the river drivers drove their logs down to the mills. In the winter of 1864 the mercury kept down below zero for nearly three months without any let up. There was no snow to speak of, and sleighing and skating parties on the river were all the rage.

But the winter of 1816 was the most dismal and severe of his recollection. Summer frosts and cold weather in early fall destroyed all crops and provision of all kinds were fearfully high. Corn cost 15 shillings a bushel, and was so scarce at that that no one could buy more than half a bushel at a time. Flour, a luxury in those days, cost $28 a barrel. The weather was terribly severe, and snowstorm followed snowstorm.

Mr. Bryant is satisfied that there has been a radical change in the climate of Maine within his life. He says we get no such long stretches of cold weather and that our snowstorms are but squalls in comparison with blocking storms of his earlier days.

OLD PEOPLE IN A GROUP. They tell what kind of weather Vermont has had.

Rutland, Jan. 18.—The oldest inhabitants of Rutland and vicinity have been interviewed in reference to the varying conditions of the weather in past years. While they could remember many mild and hard winters, and would narrate incidents that occurred, but few could fix precise dates. All substantially agree that they have never seen so mild and warm a winter as the present.

The most intelligent answers were given by a family group, known as the Pooler family, an ancient family living in the village of Rutland under one roof, namely: Amasa Pooler, age 92; Seth Pooler, 86; Mrs. Seth Pooler, 83, and Mrs. Charles R. Ladd, a sister, 81.

Amasa pooler, aged 92, who is very deaf was told the object of the visit and handed the letter of instruction to read that he might more readily understand. He took it and immediately read it aloud in a strong voice, without the aid of glasses, remarking that his second sight had come within the past two months.

He said he had seen several open, or “barefooted” winters, but could not tell the years. The winters of 1834 and 1835 were mild, with little sleighing. In 183_ he though the winter mild, but the summer was cold and frosty.

Mr. Pooler said the winter of 1815-16, after the war with Great Britain, was in many respects the most eventful. He with two brothers slept in one bed in an openly built house, and it was no infrequent thing to have their bed covered with snow that winter. A snow storm prevailed during the day of the 19th of May, when the farmers were ploughing their fields.

In 1816 there was a snow storm, April 12, and snow lay upon the ground and made good sleighing for nearly a week. June 11 another snowstorm came, and corn was cut down twice by frost, and severe frosts occurred. In 1829 snow came the next day after Thanksgiving and remained all winter.

Seth Pooler, a teacher from 1836 to 1882, said he was a member of the Massachusetts Legislature in 1858 and the winter was very cold. Snow fell Nov.5 to a depth to make good sleighing and remained all winter.

BATHING IN JANUARY. Plymouth Looms Up with a Startling Weather Story.

Plymouth (and Gloucester mention), Jan. 18.—According to the “oldest inhabitant” the severest “cold snap” ever known in these parts was in January 1857. In the neighboring town of Kingston the thermometer registered 28 degrees below zero on the morning of the 24t.h. For an entire week the trains were blockaded by snow, and the cold was intense.

Perhaps the longest stretch of cold weather remembered by those now on the stage came in February, 1871, when the harbor was frozen over for about three weeks, which circumstance was regarded as a good test of the winter’s severity. A fleet of 30 or 40 fishing vessels hailing from Gloucester and thereabouts, was imprisoned in the ice during this time, and provisions were hauled in sleds over the frozen crust to the ice bound mariners.

An exceptionally mild winter which is recalled by those who keep weather records, was that of 1875-76. On Jan. 1, 1876, a party of boys went in bathing from the end of Long wharf.

Regarding the present winter, there is but one opinion among the old-timers and that is it is an extraordinary one, and defies the powers of the most astute local weather prophet.

NO CUT FODDER YET. Some Rhode Island Farmers Lucky in the Phenomenal Weather.

Providence, Jan.18.- Judge Eli Aylsworth, who was born in 1802, and who is an active business as president of the Westminster Bank, said today that the present winter exceeds in mildness any winter that he knows of, and that he can remember back for 80 years. The wet weather of the summer had a good deal to do with the present soft atmosphere he thinks, otherwise he can’t account for it. The hardest winter in his recollection was that of 1812, and the most open was that of 1815. In 1840 there was a hard winter and the weather was continually bitter for a long period.

“But,” says Judge Aylsworth, “we have not had the hard weather in 50 years that we had each winter along from 1812 up to ’40. Along back in the 1820s and 30s we had to break out roads and it was customary to have a three-days’ blockade at times and the weather was intensely cold. The bad weather was lasting then and not so changeable as during the past few years. The 365 days in the last year had only 52 days of clear sky, only one day a week. Some of our customers from out of town report that they are herding cattle in the open fields and that the grass is as green as a spring growth. Some farmers have used no cut fodder at all as yet. The winter of 1812 began Sept. 6th.”

CLASSIC PORTSMOUTH Sends Up Stories That Sound True and Look Reasonable

Portsmouth, Jan. 18—From conversations with several of our elder citizens, whose memories range back all the way from 60-75 year, it appears that the winters of 1868 and 1869 very closely resembled those of 1878-79, and the present winter as far as it has got except that none of the old residents remember anything about la grippe having prevailed at the former dates, or that much consternation was caused among ice dealers or ice users then.

For a cold winter, that of 1857 seems to be given the palm by general consent. The workmen at the navy yard that winter, when bound to the yard, had to land their boat on Pumpkin Island (now, by some hocus-pocus put down on the charts of the harbor as “Squash” island), and leaving them there walk across the ice to the yard; and their only landing place on this side of the river, the docks being frozen over sold for several weeks, was at the navy landing at the foot of Daniel street. The ice on the eastern side of the river extended out from 50 to 500 feet; the blockade on the inside channel, West side of the river, extended from Pier wharf to Four Tree island, and from the bridge across the Sagamore to the Wentworth House at Newcastle. In January of that year, for the first and last time in the history of the Piscataqua river, men crossed it from side to side on the ice: it did not freeze over, but the drift ice from the sea blocked up against Portsmouth bridge, and the intense cold cemented it into a mass solid enough to be travelled over; and hundreds on hundreds made the trip, “just to say they had done it.” The blockade held for two tides, and then went down river again in pieces. This was the year the harbors of Boston and New York were frozen over solid for many weeks, and the day of the big “freeze over” was one of the coldest ever known here, 27 degrees below zero.

On the ponds in this vicinity, which were continuously ice bound during this winter, there were several “carnivals” on a small scale: and citizens who had not had skates on for years, some of them for half a century, were regular visitors to the ponds. Among them were the late Samuel Grav, Hon. Peter Jenners, Rev. Dr. Burroughs, and others than whom none in the city stood higher.

One of the worst snowstorms in the memory of Gen. Josiah G. Haley, the oldest representative in the state of the old-line stage drivers, and the oldest living ex-member of the Portsmouth fire department, was in January, 1866. The railroads were blockaded for from three to five days. The streets of the city were also impassable for a week, and the night of the storm scores of people were bewildered in trying to reach their homes, and were only saved by the night watch, who patrolled all night, in pairs with lanterns and shovels to render aid. It was regarded at the time as almost miraculous that no lives were lost.

SCIENCE STEPS IN. Charles Breck of Milton Keeps a Record of 40 years

Milton, Jan. — Charles Breck of Milton, hale and vigorous in his 92nd year, was seen by a Globe reporter, to whom the old gentlemen showed a notebook in which he has kept a daily record of the temperature and meteorological conditions during the past 40 years. His observations have been taken at sunrise and at 1 pm.

During the 10 years from 1849-1859 the average temperature was 48.21; for the following 10 years, 48.40; for the succeeding 10 years 49.18; and for the 10 years from 1879-1889, 49.71. The warmest year of the 40 was 1877, when the average was 51.21; the coldest was 1868 when the average was 4-.39.

These observations have been taken at his home in Milton Centre. Mr. Breck thinks that the last Christmas day was the warmest since 1829.

SLEIGHING ALL WINTER. Also a Winter When There was none at All in Keene.

Keene, Jan. 18. – Although the present winter is a most remarkable one, it is not unprecedented. Exceptionally severe or open winters appear to have occurred from time immemorial. One of our oldest inhabitants, and the one who has the best data for reference of any one we know, is Joshua D. Colony, the present senior proprietor of the Cheshire Republican. He is 95 years of age and says:

“I can remember some very cold and some very open winters. The winter of 1836 was the longest coldest and most severe of any in my recollections. Seven inches of snow fell Nov. 23, 1835 which made good sleighing and lasted without intermission until the middle of April. A large quantity of snow fell during the winter and drifted badly. The average depth of snow the first of April was two and a half feet.

“The winters of 1827 and 1849 were warm and open. Very little snow fell in either winter. The month of January 18_8 was the warmest of any within my recollection. There was but a sprinkling of snow during the month and no sleighing. There were 12 fair, warm, very warm and moderately warm days and eight cloudy and rainy days. The night of the 16th was fair, and so warm that water that stood out did not freeze.”

NEVER SAW THE LIKE. Old Green Mountaineers Talk of the Big Snows of the Past

St. Johnsbury, Jan. 18 – “We have never been cheated out of a winter in Vermont yet,” remarked Col. Frederick Fletcher, a sturdy veteran of 85 snowy winters amid the Green Mountains. “But this year is a remarkable one. The year 1807 was remarkable in Vermont for its cold weather and great snow-fall. Then, also, 1816 is famous for its hard winter. On June 8 of that year five inches of snow fell, and it was so cold that vegetation was completely ruined. The last two winters have been remarkably open and mild.”

David Trull, who has kept a daily record of the wandering course of the mercury for nearly half a century, gives some interesting figures from his experience. Mr. Trull said: “1862 and 1863 were hard winters. A man in this section had a tunnel between his house and barn. On Jan. 1 in 1862, 14 inches of snow fell. In 1878, we had a remarkably forward spring which shortened up the winter considerably.”

Dr. H. An. Cutting of Lunenburg, who was formerly State geologist, and makes a specialty of the weather, says, “The winter of 1844 was a severe one. We had a big snowstorm on the 1st day of April, and the snow would average four feet deep on a level. In 1871 we had the thermometer 40 below zero, and a lively thunderstorm, both in the month of February. The coldest weather on record here was Dec. 25, 1872, when the thermometer actually registered 50 below zero.

E. F. Brown, an old resident, said that in 1863 there was a lively snow storm on Oct 20: “I remember I was in Montpelier at the General Assembly and when I started home in a team—there was no railroad then—it began to snow. We stopped at Cabot over night, and when we headed for home in the morning the snow as as high as the hubs. It stayed on the ground until spring, too! Winter before last as a snug one, and its length taxed the coal bins to their utmost.”

GROUND CRACKED LIKE PISTOL SHOTS.

Woburn, Jan. 18. Elijah Wyman, over 83 years old, says that the hardest winter he remembers was in 1835, the winter of the big fire in New York. The ground froze very hard and cracked, causing a noise like pistol shots, and the same season four feet of snow remained until nearly March 1. In December of that year he remembers riding into Boston when the glasses showed 35 degrees below zero. Large cracks were found in the ground after the snow thawed.

Boston Globe, 1890. “WINTERS OF YORE: Strange Freaks of the Weather. Freezing the old Ocean. Talks with a Hundred Oldest Inhabitants. Many Never Saw it Milder than Now. Coasting from Second Story Windows—January Bathing.”

- Photo credit for Britannia: lithograph from sketch by J. C. King, A. de Vaudricourt, Bouve & Sharp – https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/148835.html This Print representing the B & N.A. Royal Mail Steamship Britannia John Hewitt, Commander, leaving her dock at East Boston on the 3rd of February 1844 on her voyage to Liverpool (through) a canal cut in the ice 7 miles long [collection Royal Museums Greenwich] Paddle Steamer Britannia, Cunard’s 1st liner

“Mr. Pooler said the winter of 1815-16, after the war with Great Britain, was in many respects the most eventful. He with two brothers slept in one bed in an openly built house, and it was no infrequent thing to have their bed covered with snow that winter.”

excerpt from1890 interview- Rutland, VT

[*see Russian Flu comp: 1918 PANDEMIC: RECONSTRUCTING HOW THE FLU RAGED THEN FLATTENED IN GLOUCESTER MASSACHUSETTS WHEN 183 DIED IN 6 WEEKS, March 2020, republished GMG, May 2020.]