By Matt Schudel WASHINGTON POST JULY 23, 2018

By Matt Schudel WASHINGTON POST JULY 23, 2018

WASHINGTON — Lincoln Brower, one of the foremost experts on the monarch butterfly, who spent six decades studying the life cycle of the delicate orange-and-black insect and later led efforts to preserve its winter habitat in a mountainous region of Mexico, died July 17 at his home in Nelson County, Va. He was 86.

He had Parkinson’s disease, said his wife, Linda Fink.

Dr. Brower, who taught at Amherst College in Massachusetts and the University of Florida before becoming a research professor at Virginia’s Sweet Briar College in 1997, began studying the monarch butterfly in the 1950s.

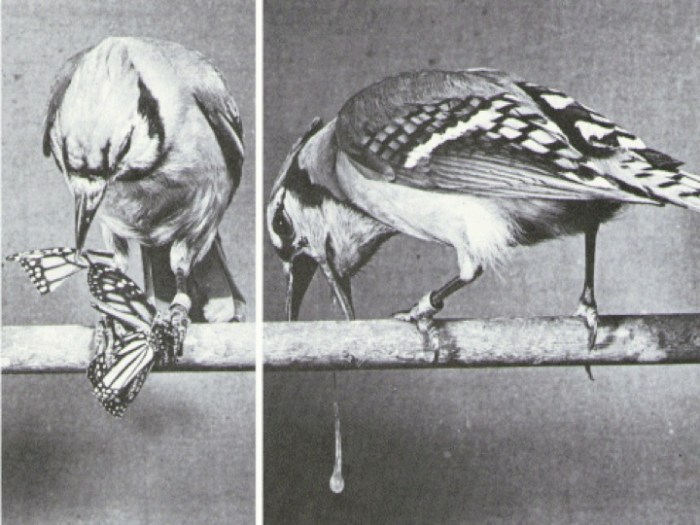

He made key discoveries about how it protected itself by converting a toxic compound from its sole food source, the milkweed plant, into a chemical compound that sickened its predators, primarily birds.

Dr. Brower’s famous “Barfing Bluejay” photo of a bird wretching after eating Monarchs, proved Monarchs don’t tast good. Dr. Lincoln Brower photo.

In the 1970s, other scientists discovered that monarchs had extraordinary migratory powers, more like birds or whales than insects. Each fall, monarchs from east of the Rocky Mountains travel thousands of miles to a Mexican forest, where they spend the winters. Monarchs from western North America migrate to California.

‘‘It has the most complicated migration of any insect known,’’ Dr. Brower told the Chicago Tribune in 1998. ‘‘Somehow they know how to get to the same trees every year. It’s a highly specific behavior that is unique to the monarch butterfly.’’

It takes three to four generations of monarchs to complete the one-year life cycle. After the migration to Mexico, the butterflies begin their return trip to North America, and a new generation is born en route, growing from larvae to caterpillars before taking flight.

With the arrival of cooler weather in the fall, the great-grandchildren of the monarchs that flew south the previous year will make the same trip, returning to the mountainsides visited by their ancestors.

‘‘It’s an inherited pattern of behavior and a system of navigation that we don’t really understand,’’ Dr. Brower said in 2007. ‘‘We don’t know exactly how they find their way. We don’t know how they know where to stop.’’

Dr. Brower first visited the monarchs’ winter quarters in a Mexican forest, about 80 to 100 miles west of Mexico City, in 1977. At an elevation of 9,500 to 11,000 feet, tall fir trees were entirely covered by hundreds of millions of butterflies.

When they stir their wings, ‘‘it sort of sounds like leaves blowing in the fall,’’ said Dr. Brower’s son, Andrew Brower, a biologist and butterfly expert at Middle Tennessee State University, in an interview. ‘‘It’s remarkable. You look up, and the sky is blue, but then it’s orange. It’s like an orange stained-glass window above your head.’’

During more than 50 trips to Mexico to study monarchs, Dr. Brower began to see that their numbers were shrinking.

In North America, Dr. Brower also pointed out, the monarchs face a further problem from the growing use of herbicide, which has eradicated much of their food source, the once-abundant milkweed.

There are still millions of monarchs in North America, but their numbers fluctuate from year to year, in an ever-downward trend. By some counts, the population has fallen by as much as 90 percent since the 1980s.

Dr. Brower joined efforts by environmental groups to have the monarch recognized as a ‘‘threatened’’ species.

Lincoln Pierson Brower was born Sept. 10, 1931, in Madison, N.J. His parents had a nursery and rose-growing business. He was 5 when he took notice of an American copper butterfly landing on a clover bloom. ‘‘I just stared at that tiny butterfly, and it was so beautiful to me,’’ he told NPR. ‘‘And that was the beginning.’’

He graduated from Princeton University in 1952, then received a doctorate in zoology from Yale University in 1957. Some of his early scientific papers were written with his first wife, the former Jane Van Zandt. That marriage ended in divorce, as did a second, to Christine Moffitt.

Mr. Brower leaves his wife of 27 years, Linda Fink, a professor of ecology at Sweet Briar College and a frequent scientific collaborator; two children from his first marriage, Andrew Brower of Christiana, Tenn., and Tamsin Barrett of Salem, N.H.; a brother; and two grandchildren.

READ MORE HERE:

Dr. Lincoln