Lovely long weekend with my family, cooking great dinners and long beach walks. Oh how I’ll miss my daughter when she returns to Santa Monica. All photos Liv Hauck

Tag: tom

POST FOR GMG FOB DAVE IN RESPONSE TO HIS QUESTION ABOUT WHY THERE WERE NO WILD TURKEYS ON CAPE ANN IN HIS YOUTH

GMG Reader Dave wrote recently saying that he did not recall seeing turkeys on Cape Ann when he was growing up. Although the Eastern Wild Turkey is native to Massachusetts, it was rarely seen after 1800 and was completely extirpated by 1851.

GMG Reader Dave wrote recently saying that he did not recall seeing turkeys on Cape Ann when he was growing up. Although the Eastern Wild Turkey is native to Massachusetts, it was rarely seen after 1800 and was completely extirpated by 1851.

The Wild Turkey reintroduction to Massachusetts is a fantastic conservation success story and a tremendous example of why departments of conservation and protection are so vital to our quality of life.

Massachusetts was recently ranked the number one state by U.S. News and World Report and conservation stories like the following are shining examples of just one of the many zillion reasons why (healthcare and education are the top reasons, but conservation IMO is equally as important).

Reposted from the Wild Turkey FAQ page of the office of the Energy and Environmental Affairs website.

“At the time of Colonial settlement, wild turkeys were found nearly throughout Massachusetts. They were probably absent from Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, and perhaps the higher mountain areas in the northwest part of the state. As settlement progressed and land was cleared for buildings and agriculture, turkey populations diminished. By 1800, turkeys were quite rare in Massachusetts, and by 1851 they had disappeared.

Between 1911 and 1967 at least 9 attempts in 5 counties were undertaken to restore turkeys to Massachusetts. Eight failed (probably because of the use of pen-raised stock; and one established a very marginal population which persisted only with supplemental feeding.

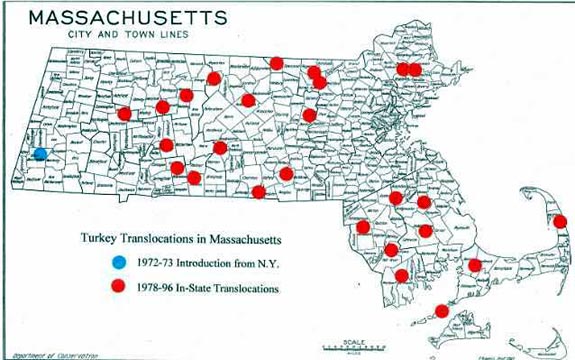

In 1972-73, with the cooperation of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, MassWildlife personnel live-trapped 37 turkeys in southwestern New York and released them in Beartown State Forest in southern Berkshire County. By 1976, these birds had successfully established themselves and by 1978 this restoration effort was declared a success.

Beginning in 1978, MassWildlife began live-trapping turkeys from the Berkshires and releasing them in other suitable habitat statewide. Between 1979 and 1996, a total of 26 releases involving 561 turkeys (192 males, 369 females) were made in 10 counties (see the following Table and the accompanying map).

| Turkey Transplants within Massachusetts 1979-1996 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Town | County | Year | Number (Sex) |

| Hubbardston State Forest | Hubbardston | Worcester | 1979, 1981 | 22 (10M, 12F) |

| D.A.R. State Forest | Goshen | Hampshire | 1981-82 | 14 (6M, 8F) |

| Mt. Toby State Forest | Sunderland | Franklin | 1982 | 22 (7M, 15F) |

| Holyoke Range | Granby | Hampshire | 1982 | 24 (8M, 16F) |

| West Brookfield State Forest | West Brookfield | Worcester | 1982-83 | 24 (12M, 12F) |

| Miller’s River Wildlife Management Area | Athol | Worcester | 1982-83 | 24 (11M, 13F) |

| Koebke Road | Dudley | Worcester | 1983 | 25 (7M, 18F) |

| Groton Fire Tower | Groton | Middlesex | 1984 | 21 (10M, 11F) |

| Rocky Gutter Wildlife Management Area | Middleborough | Plymouth | 1985-86 | 25 (12M, 13F) |

| Bolton Flats Wildlife Management Area | Bolton | Worcester | 1986-87 | 24 (8M, 16F) |

| Naushon Island | Gosnold | Dukes | 1987 | 22 (6M, 16F) |

| John C. Phillips Wildlife Sanctuary | Boxford | Essex | 1988 | 21 (9M, 12F) |

| Fall River-Freetown State Forest | Fall River | Bristol | 1988 | 24 (11M, 13F) |

| Baralock Hill | Groton | Middlesex | 1988 | 16 (5M, 11F) |

| Camp Edwards Army Base | Bourne/Sandwich | Barnstable | 1989 | 18 (6M, 12F) |

| Jones Hill | Ashby | Middlesex | 1990 | 20 (7M, 13F) |

| Whittier Hill | Sutton | Worcester | 1990 | 22 (9M, 13F) |

| Conant Brook Reservoir | Monson | Hampden | 1991 | 27 (3M, 24F) |

| Bradley Palmer State Park | Topsfield | Essex | 1991 | 18 (1M, 17F) |

| Hockomock Swamp and Erwin Wilder WMA | West Bridgewater | Plymouth | 1992-93 | 24 (5M, 19F) |

| Slade’s Corner | Dartmouth | Bristol | 1993 | 23 (10M, 13F) |

| Wendell State Forest | Wendell | Franklin | 1993 | 19 (4M, 15F) |

| Facing Rock Wildlife Management Area | Ludlow | Hampden | 1994 | 8 (1M, 7F) |

| Peterson Swamp Wildlife Management Area | Halifax | Plymouth . | 1994 | 26 (11M, 15F) |

| Cape Cod National Seashore | Wellfleet | Barnstable | 1995-96 | 28 (5M, 23F) |

| Terrybrooke Farm | Rehoboth | Bristol | 1996 | 20 (8M, 12F) |

| Totals | 561; (192M, 369F) | |||

By 1996, turkeys were found in Massachusetts about everywhere from Worcester County westward, except in the immediate vicinity of Springfield and Worcester. Good populations are also now found in suitable, but more fragmented, habitats in Bristol, Essex, Middlesex, and Plymouth Counties. On Cape Cod, Barnstable County, turkeys may be found on and near the Massachusetts Military Reservation and the Cape Cod National Seashore. These birds have also moved northward from releases in Plymouth County into southern Norfolk County. On Martha’s Vineyard, wild-strain birds are absent; however, feral pen-raised birds may be found over much of the island. Turkeys are absent from Nantucket and Suffolk Counties. The average statewide fall turkey population is about 18,000-20,000 birds.

Land-use changes have historically influenced the population and distribution of the wild turkey and other wildlife. Such changes will continue to affect the natural environment. For a historical perspective, see the references by Cardoza (1976) and Cronon (1983).”

TURKEY BROMANCE

From far across the marsh, large brown moving shapes were spotted. I just had to pull over to investigate and was happily surprised to see a flock of perhaps a dozen male turkeys all puffed up and struttin’ their stuff. I headed over to the opposite side of the marsh in hopes of getting a closer look at what was going on.

Turkey hen foraging

Found along the edge, where the marsh met the woodlands, were the objects of desire. A flock of approximately an equal number of hens were foraging for insects and vegetation in the sun-warmed moist earth.

Males begin exhibiting mating behavior as early as late February and courtship was full underway on this unusually warm February morning. The funny thing was, the toms were not fighting over the hens, as you might imagine. Instead the males seemed to be paired off, bonded to each other and working together, strategically placing themselves in close proximity to the females. A series of gobbles and calls from the males closest to the females set off a chain reaction of calls to the toms less close. The last to respond were the toms furthest away from the females, the ones still in the marsh. It was utterly fascinating to watch and I tried to get as much footage as possible while standing as stone still for as long as is humanly possible.

With much curiosity, and as soon as a spare moment was found, I read several interesting articles on the complex social behavior of Wild Turkeys and it is true, the males were bromancing, as much as they were romancing.

Ninety percent of all birds form some sort of male-female bond. From my reading I learned that Wild Turkeys do not. The females nest and care for the poults entirely on her own. The dominant male in a pair, and the less dominant of the two, will mate with the same female. Wild Turkey male bonding had been observed for some time however, the female can hold sperm for up to fifty days, so without DNA testing it was difficult to know who was the parent of her offspring. DNA tests show that the eggs are often fertilized by more than one male. This behavior insures greater genetic diversity. And it has been shown that bromancing males produce a proportionately greater number of offspring than males that court on their own. Poult mortality is extremely high. The Wild Turkey bromance mating strategy produces a greater number of young and is nature’s way of insuring future generations.

The snood is the cone shaped bump on the crown of the tom’s head (see below).

The wattle (or dewlap) is the flap of skin under the beak. Caruncles are the wart-like bumps covering the tom’s head. What are referred to as the “major” caruncles are the large growths that lie beneath the wattle. When passions are aroused, the caruncles become engorged, turning brilliant red, and the snood is extended. The snood can grow twelve inches in a matter of moments. In the first photo below you can see the snood draped over the beak and in the second, a tom with an even longer snood.

It’s all in the snood, the longer the snood, the more attractive the female finds the male.

It’s all in the snood, the longer the snood, the more attractive the female finds the male.

Male Turkey not puffed up and snood retracted.

Male Turkey not puffed up and snood retracted.

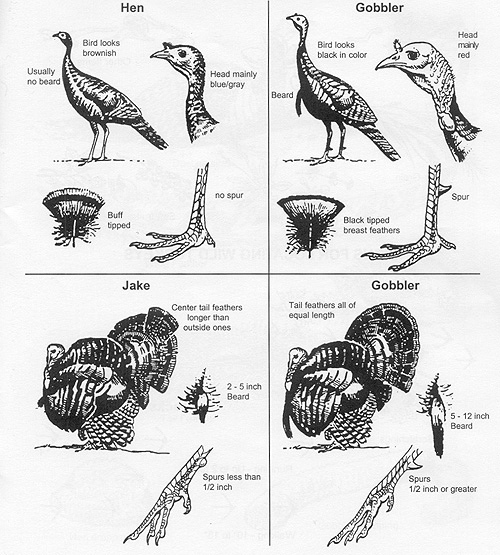

A young male turkey is called a jake and its beard is usually not longer than a few inches. The longer the beard, generally speaking, the older the turkey. Male Wild Turkey, with beard and leg spurs.

Male Wild Turkey, with beard and leg spurs.

Male Wild Turkeys with snood extended (foreground) and snood retracted (background).

When the butt end is prettier than the face

When the butt end is prettier than the face

In case you are unsure on how to tell the difference between male (called tom or gobbler) and female (hen), compare the top two photos. The tom has a snood, large caruncles, carunculate (bumpy) skin around the face, and a pronounced beard. The hen does not. Gobblers also have sharp spurs on the back of their legs and hens do not.

Read more here:

http://www.alankrakauer.org/?p=1108

http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2005/03/02_turkeys.shtml

http://www.mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/dfw/fish-wildlife-plants/wild-turkey-faq.html