This excerpt has been adapted from 1918 Pandemic: Reconstructing How the Flu Raged Then Flattened in Gloucester, Massachusetts when 183 Died in 6 weeks, HERE by Catherine Ryan. Mini posts like this one highlight select weeks during the outbreak as serialized quick reads about this Gloucester history.

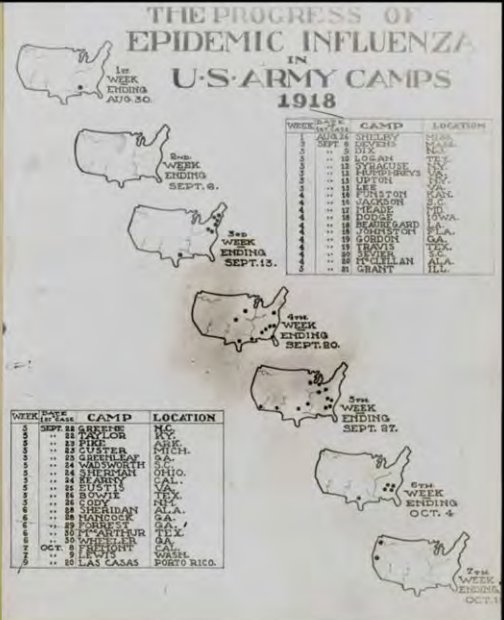

The flu’s arrival in Gloucester during the second wave was more or less timed with Massachusetts outbreaks at military installations and Labor Day.

Boston Navy Yards

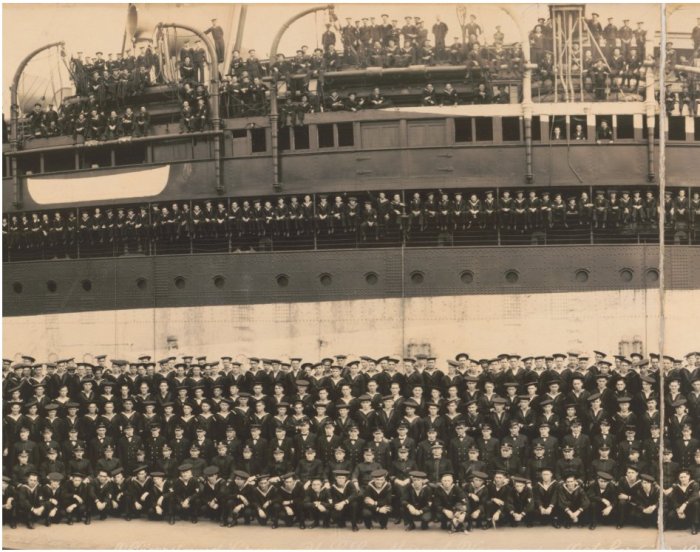

Densely populated bases and transports weren’t ideal sanitary environments. The Navy yards in Boston and vicinity were among America’s busiest for transportation of troops and supplies during WWI.

At the time of this aerial photograph circa 1906, the Navy Yards were called the Charlestown Navy Yard.

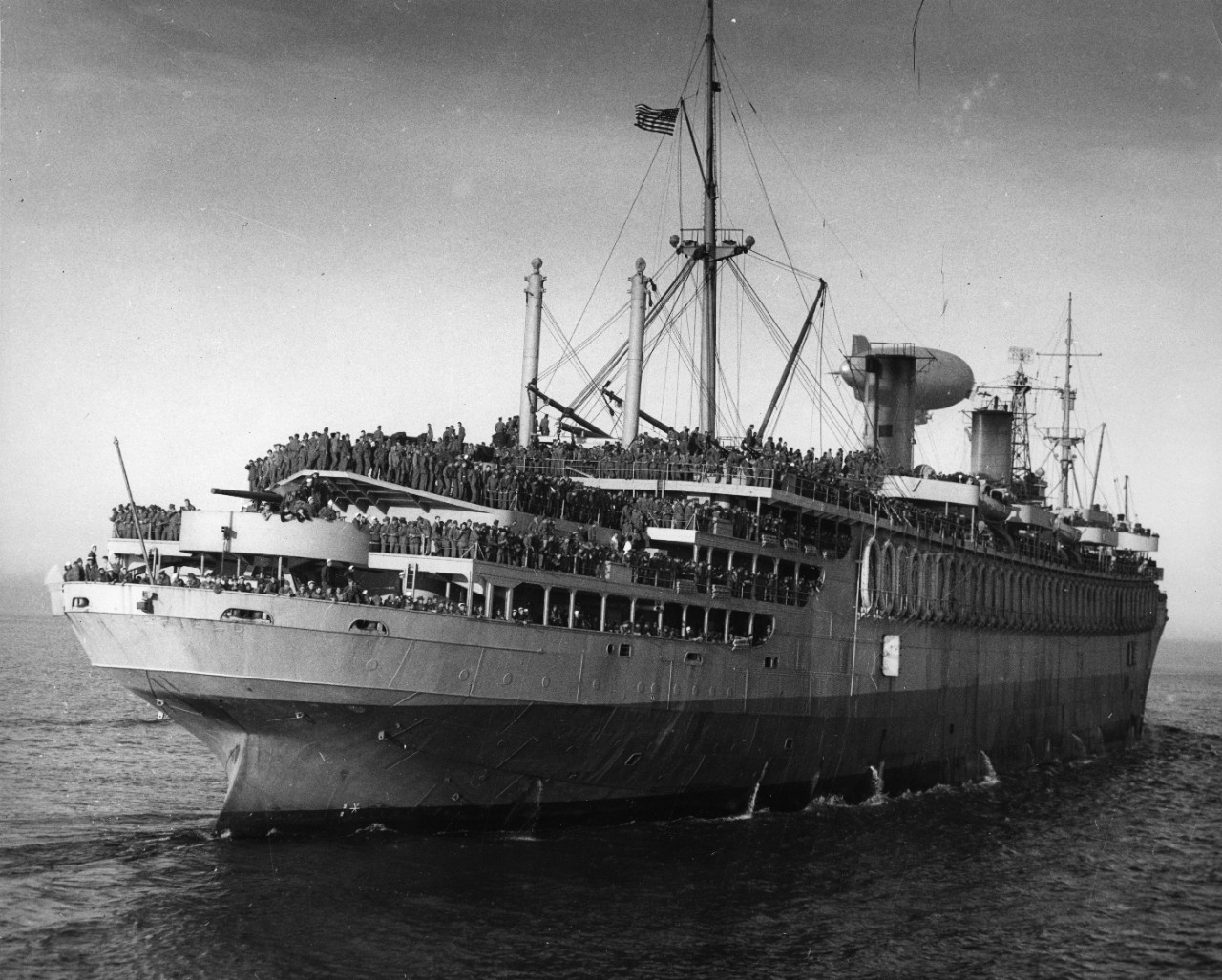

Vintage WWI embarkation and return photographs give a better idea of the scale of the operation of war: vessels are teeming with enlisted men squeezed shoulder to shoulder, potential carriers.

Library of Congress 15

In August of 1918, Navy sailors shoreside were hospitalized in Boston with a flu so contagious that dozens at a time were admitted, and 1200 died by early October. The following brief account about the Boston outbreak was written in 1920 by Warren T. Vaughan, Preventative Medicine and Hygiene Department of the Harvard Medical School. His book, Influenza: An Epidemiological Study, was published by the American Journal of Hygiene in 1921. This Pandemic 1918 essential read includes Vaughan’s research investigating an outbreak at Camp Sevier in South Carolina, and a massive civilian census–thanks to a grant from Met Life– in Boston following the 1919 wave. (Vaughan was a physician at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital when he was drafted May 29, 1917; he advanced to lieutenant colonel.)

“Autumn Spread in the United States 1918

By the first of July, 1918, convalescent cases of influenza began to appear among members of the crews of transports and other vessels arriving in Boston from European parts. The number of such cases on each ship was usually not more than four or five, but Woodward records that in one or two instances between twenty and twenty-five individuals were sick on incoming vessels. None of these were seriously ill, none were sent to the hospital, and none died. The disease in this class of persons did not become severe until late August. Woodward has found on inquiry among practicing physicians that typical cases of influenza were seen with notable frequency in private practice in the vicinity of Boston during the month of August, and that they had developed no serious complications, the only after effect being the marked prostration. These mild preliminary cases failed to attract attention; first, because of their relative scarcity, and second because of their benign character. Public attention was first directed to the influenza in Boston by the apparently sudden appearance during the week ending August 28th of about fifty cases at the Naval station at Commonwealth Pier. Within the next two weeks over 2000 cases had occurred in the Naval forces of the First Naval district. One week later there was a similar sudden outbreak in the Aviation School and among the Naval Radio men at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The first death in Boston was reported on September 8th. The peak of daily incidence in Boston occurred around the first of October. In the week ending October 5th a total of 1,214 deaths from influenza and pneumonia was reported, while by the third week of October this total had fallen to less than 600, and for the week ending November 9th was down to 47…On or about December 1st the incidence again rose and continued increasing daily, to reach its peak in a severe recrudescence around December 31…”, and “A sudden and very significant increase was reported during the third week in August in the number of cases of pneumonia occurring in the army cantonment at Camp Devens, seeming to justify the statement that an influenza epidemic may have started among the soldiers there even before it appeared in the naval force…” 16

Warren T. Vaughan

Library of Congress

Sea of men [Officers and crew, U.S.S. Mount Vernon, October 30, 1918, Crosby, J. C., photographer. The author’s grandfather served on this ship. Library of Congress]

Fort Devens

Besides the naval bases in Boston, Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, was another military epicenter with fierce contagion and fast deaths; an estimated 15,000 men were infected by the flu and more than 800 died. Fort Devens was one of the country’s largest WW1 military bases, serving tens of thousands of soldiers in transition. According to the War Department research in 1926, “Accommodations were provided for only 36,000 men, but this figure often was exceeded, more especially in August and September 1918 when the strength was approximately 45,000 and 48,000 respectively.” Fort Devens housed the prisoners of war, also.

The base looks nearly a metropolis in vintage photographs. A selection of interior (clean!) and exterior shots were taken before the storm of flu. 18

Barracks at Camp Devens, Ayer, Mass. Camp Devens, near Ayer, Massachusetts, was one of those national army camps that had a miraculous and mushroom growth during the summer of 1917, when everything had to be done with a rush to train our boys for the great combat overseas. In ten weeks time, 5000 men, on a weekly payroll of $100,000, built 1,400 buildings, laid 20 miles of road, 400 miles of electric wiring, 60 miles of heating pipes, and installed 2200 shower baths. All of this work was accomplished in time for the cantonement [sic] to receive 40,000 men early in September, 1917, when the first selective draft men were impressed into service, a service which the patriotism of most led them to embrace willingly and without a murmur. The camp was a veritable city, and a well built one for its purposes. It had a post office, telegraph and telephone service, police station, guard house, fire department and hospital, all directed and manned by service men. The auditorium seated 3000 men, and the base hospital treated at times as many as 800 men in a single day. Bare and uninviting as the camp was to men accustomed to the comforts, and in many instances the luxuries of home, it provided an unusual degree of comfort to men in training for military service. The laundries and central power plant with its great furnaces are installed in the buildings with high chimneys which we see in the distance. The soldiers in the foreground were using a leisure hour to write home, for in the intervals of training it was to home that their thought turned, and at home parents and sweethearts always eagerly awaited letters.

‘Barracks at Camp Devens, Boys on Hillside Writing Letters, Ayer, Mass.’ the Keystone View Company stereograph card, includes a write up about the barracks verso

As with the navy images, photographs of separate divisions illustrate the density at these camps and impossibility of social distancing in some environments.

Library of Congress19

Portraits of divisions as thick as forests help to illustrate the shattering descriptions expressed by front line responders confronting so many felled by flu. Camp physician, Roy Grist, related “boys laid out in long rows, ” 20 and Dr. Victor C. Vaughan recounted bodies “stacked like cord wood” in his autobiography published in 1926.

“…In the memory chambers of my brain there hang many pictures. Some are the joy of my life, too sacred and too personal to describe to any save my most intimate friends. But there are also ghastly ones which I would tear down and destroy were I able to do so, but this is beyond my power…While I am engaged in describing the horrors of my memory picture gallery I might as well say something of the others, and then I will promise never to touch this gruesome subject again…The fourth canvas is quite as large as the others. I see hundreds of young, stalwart men in the uniform of their country coming into the wards of the hospital in groups of ten or more. They are placed on the cots until every bed is full and yet others crowd in. The faces soon wear a bluish cast; a distressing cough brings up the blood stained sputum. In the morning the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood. This picture was painted on my memory cells at the division hospital, Camp Devens, 1918, when the deadly influenza demonstrated the inferiority of human inventions in the destruction of human life.” 21

Victor C. Vaughan

As Dean of the University of Michigan School of Medicine and director of the Surgeon General’s Office of Communicable Disease, Vaughan was sent to Camp Devens as part of the federal government’s elite assessment team. Author Carol R. Byerly who wrote The Fever of War in 2005 added in a 2010 journal article how, “Camp Devens physicians performing autopsies described influenza pathology as unique, characterized by “the intense congestion and hemorrhage” of the lungs. But as Vaughan and [John Hopkins pathologist William Henry] Welch investigated Camp Devens, the virus kept moving. Before any travel ban could be imposed, a contingent of replacement troops departed Devens for Camp Upton, Long Island, the Army’s debarkation point for France, and took influenza with them.” 23

It’s no wonder Vaughan didn’t dwell on this savage disease.

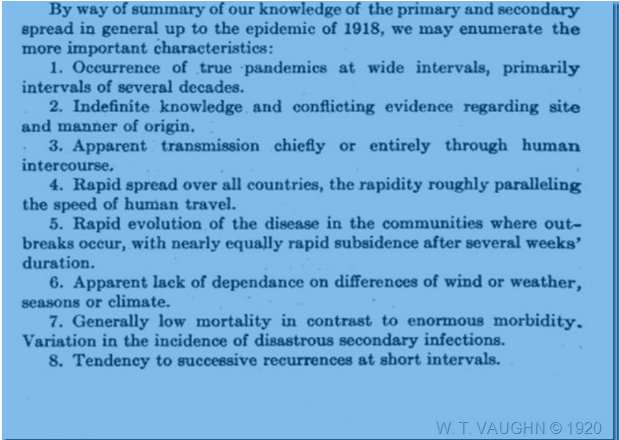

Another Vaughan, Dr. Warren T. Vaughan– who wrote in 1920 about the Boston outbreak in the Navy mentioned above– was “one of a board of officers appointed to investigate” a milder advent that “had broken out among troops stationed” in the army base at Camp Sevier, South Carolina. He explained how difficult pandemics were to predict.

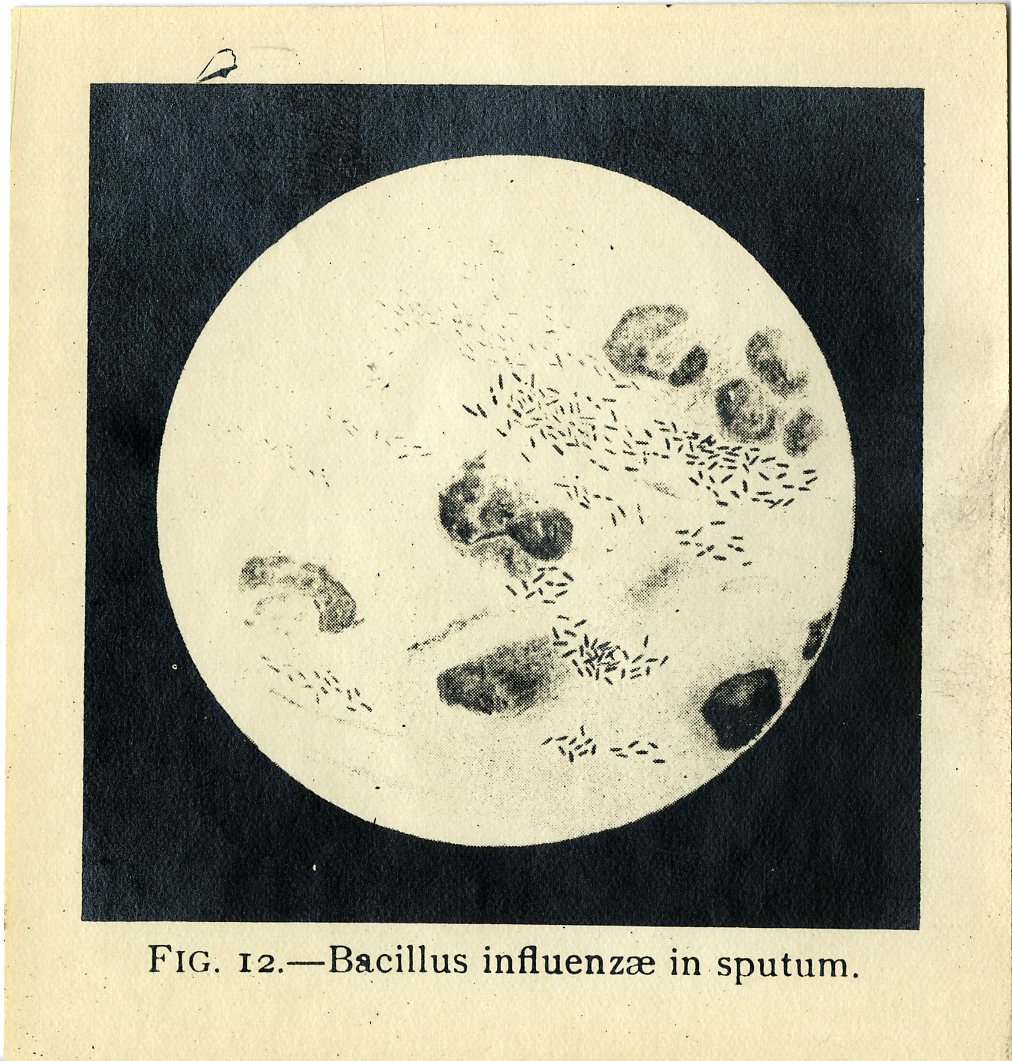

“Sudden onset regimental infirmary…careful bacteriologic examination was made at that time and predominating organisms were found to be a gram negative coccus resembling micrococcus catarrhalis, and a non-hemolytic streptococcus. They were uncomplicated cases..at the time none of us dreamed of any possible connection with a severe epidemic to occur later (at that wave bacilli weren’t present)…”

Warren T. Vaughan, 1920

National Museum of Health and Medicine-1918 infected lung preserved as wet tissue specimen

Block of medical images, various collections 24

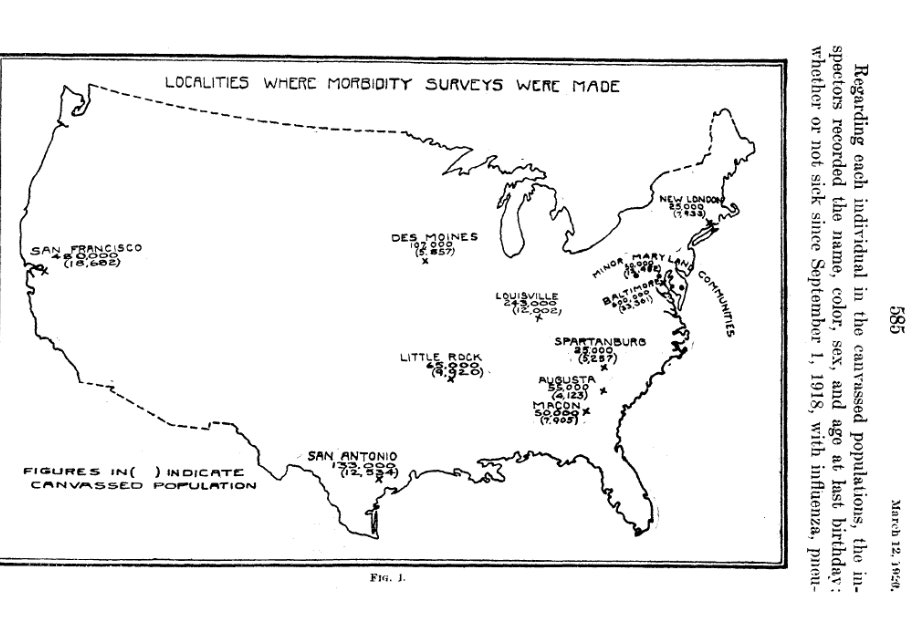

W.T. Vaughan felt not a single community in which there were reported cases reached tallying anywhere near the total of actual cases. And so he rolled up his sleeves. “Toward the end of January 1920 when recurrent epidemic as at its height in Boston,” Vaughn writes, “The author undertook with the aid of 13 trained social service workers and one physician graduate from the Harvard school of public health to make sickness census of 10,000 individuals,” in person, in six districts.

His statements from 1920 echo in today’s news:

On determining first cases of infection

“There is evidence –the collection of which has not been completed– pointing to the existence of cases of the disease in various centers, probably widely distributed, weeks before they were definitely recognized as influenza…” – Warren T. Vaughan, 1920

On healthy carriers

“Yes it does exist.” – Warren T. Vaughan, 1920

On crowd gatherings

“Yet another phenomenon which would lead us to conclude that human intercourse is the most potent factor in the transmission of influenza is the fact that there is frequently a high increase in the influenza rate following crowd gatherings. Parkes observed long ago that person in overcrowded habitations, particularly in some epidemic, suffered especially, and several instances are on record of a large school or barracks being first attacked and the disease prevailing there for some days, before it became prevalent in the towns around…In discussing the recrudescence of influenza in Boston in November and December, Woodward remarks as follows: “Whether or not it may be more than a succession of coincidences it is certainly of interest to note that the November outbreak of influenza showed itself three days after the Peace Day celebration on November 12th, when the streets, eating places and public conveyances were jammed with crowds; that the December epidemic began to manifest itself after the Thanksgiving holiday…and that reported cases mounted rapidly during the period of Christmas shopping…” Warren T. Vaughan, 1920

By way of summary

Looking for signposts | on the manner of the flu’s spread

Vaughan looked to the past as he researched the present. He quoted 1847 influenza research by Thomas Watson that resonates poignantly:

“…although the general descent of the malady is, as I have said, very sudden and diffused, scattered cases of it, like the first droppings of a thunder shower, have usually been remembered as having preceded it.” Thomas Watson on Influenza, 1847 29

Local Enlisted Lads sick/ quarantined before Labor Day

Local enlisted lads wrote about the infamous flu in letters home to Gloucester, Mass., and other Cape Ann towns before Labor Day, although they weren’t read or published until after the disease exploded in Gloucester. Private John J. Smith wrote his mother, Mrs. Charles W. Smith of 5 Center Court, a long letter dated September 1, 1918. At one point he puts it plainly: “I feel better over here than I did in Camp Devens and sure have got that same good old appetite…”30 The letter appeared in the Gloucester Daily Times on the last day of September, included as part of the series, “Our Boys Write Bright Letters Home.”

Lt. J. Irving Baker from Manchester-by-the-sea wrote his mother, “Somewhere from France, July 23, 1918.” about how he was, “getting along fine now, you can tell by this paper. I went down the street myself and bought it. I have been moved into another building where I have a room with another officer. It is fine. From the window I can see hills and trees. It is a summer resort in the foothills of the Alps. There is a mineral spring here in which I hope to have a bath before I leave.” He broke off before mailing, and added an update July 31 from an Army base hospital in Allery, France, where he was sent to convalesce.

“We just arrived at the convalescent camp and are pretty tired, did not get much chance to sleep on the train. This is a small place called Allery [sic] about 180 miles northeast of Flermont. It looks a good deal like an army cantonment with wooden barracks, partitioned into rooms, tow in a room. The town is only a station, cafe and a few houses…You know I lost nearly all my things when I came to the hospital, I am managing to get a kit together after a fashion. …They raise many geese in this section of France…Aug. 5. I am feeling fine now, only short of breath when I go up stairs or exert myself–as I’m pretty tired just now.”

The letter was published in the Manchester Cricket on September 21, 1918 within a column devoted to “Letters From Our Boys at the Front”.

Allery [sic] photo, WWI Centennial Commission31

Another soldier from Manchester, Private Wade Revere Brooks, joined the Marines. In a detailed letter from South Carolina, he described multiple quarantines at basic training camp(s) that began for him immediately upon arrival, back in June 1918, and with each new skills rotation until deployment. His undated letter was featured in the Manchester Cricket on October 26, 1918, long after the crest of the pandemic. From the contents it seems to have been written in September. He signs off:

“…After coming off the range we were held for the influenza quarantine, and we are now awaiting for shipment to Virginia where we get our overseas training, which consists of gas attack drills, hand grenade throwing and more trench work. I hope we will move soon. There are six thousand trained troops waiting for the quarantine for Flu to be lifted. Well I have told you as much as I can think of just now, so I will close hoping this will interest you some. I am sincerely yours, Pvt. Wade Revere Brooks, Company 332, Battalion O, United States Marine Corps, Paris Island, South Carolina. 32

Acting Mess Sergeant Frank A. McDonald sent a postcard from the hospital at Camp Jackson, Columbia, South Carolina, conveyed in the Gloucester Daily Times October 22, 1918 , “Many Local Boys Had the Influenza”:

“He is in the base hospital recovering from a three weeks’ serious illness of influenza. He states that Herman Amero* (illegible) is recovering after four weeks siege of pneumonia, Herbert Joyce and Robert Smith, Gloucester boys at the same camp, are also on the mending hand. The other Gloucester boys are all well, he [Frank A. McDonald] says.”

Social distancing is absent in the post office at Camp Jackson when this photograph was taken that September. Camp Jackson utilized tents for its flu management.

(Nat. Mus. of Health & Med., 1918) Camp Jackson, SC33

War news produced by the military stressed the strength in numbers of America’s fighting forces as with this 1917 photograph “Embarked for France”.

or this ‘We won’t stop coming till it’s over Over There’ image published on the front page of the Tribune Graphic September 8, 1918.

“This photograph, taken aboard one of the first American transports sailing for France has just been released by the censor. At the time Germany was still loudly boasting that we couldn’t get an army over there in time to make any difference. To-day she is singing another tune.”

Besides arriving sick, more than 12,000 enlisted died from the flu pandemic on the troop transports heading to France before they landed.35 Men in the September 1918 photograph could very well have been among the afflicted.

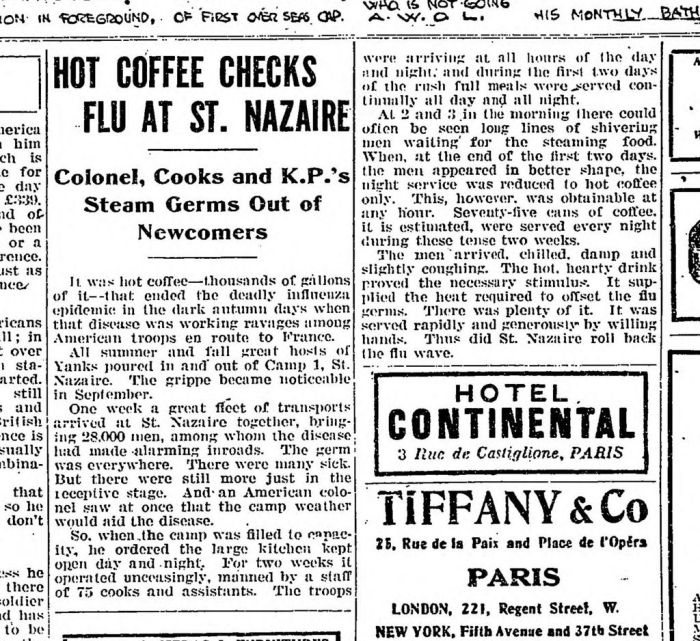

When the flu was mentioned in Stars and Stripes, the newspaper written by American servicemen for soldiers, it was late news and downplayed. This article, “Hot Coffee Checks Flu at St. Nazaire: Colonel, Cooks, and K.P’s Steam Germs Out of Newcomers”, published December 13, 1918, claimed that coffee, climate and command vanquished the deadly epidemic. “It was hot coffee—thousands of gallons of it –that ended the deadly influenza epidemic in the dark autumn days when that disease was working ravages among American troops en route to France.”

If the extent of flu deaths within the military that spring and summer were understood, the government’s fall conscription push for 15 million registrations may have been impossible. Who among us would knowingly support a draft for our sons and fathers, our brothers and friends, with such a lethal disease out of control at training camps and ships bound for France?

The records do appear to indicate that federal guidelines were mostly held back until after the September 12th national draft registration day (and the preceding parades and rallies that encouraged registration). By that date, officials including public health and infectious disease experts within the military knew key facts: that the death rate was higher in barracks and cantonments than tent camps; that quarantines were necessary at training camps; that geography was more important than cramped quarters; that healthy carriers exist; and that nurses and non commissioned suffered more than officers and privates. Gloucester would welcome and benefit from this military expertise.

Enlisted men who succumbed during training or transport, died from pneumonia or flu “in the line of duty. ”37 Still, death in battle was mourned more openly than death by disease, tamping down stories and comparisons about the flu. Efforts to reduce transmission at a time of heightened engagement in WW1 — whether communication was instantaneous (telegraph) or not; word of mouth or not; censored or not– were next to impossible by Labor Day.

Full article- 1918 Pandemic: Reconstructing How the Flu Raged Then Flattened in Gloucester, Massachusetts when 183 Died in 6 weeks

- Excerpt part 1- Labor Day crowds before the first flu death: Gloucester during the 1918 Pandemic Part 1

- Excerpt part 2 (above) Fierce contagion fast deaths Boston Navy Yards and Fort Devens

- Excerpt part 3 East Gloucester art exhibit and funeral announcement on the eve of WWI Draft Registration

- Excerpt part 4

Flu Masks / Face Masks instructions Gloucester 1918 1918 Directions for sewing face masks and the Mask Factory in #GloucesterMA | plus DIY lost sock mask 2020 – Good Morning Gloucester