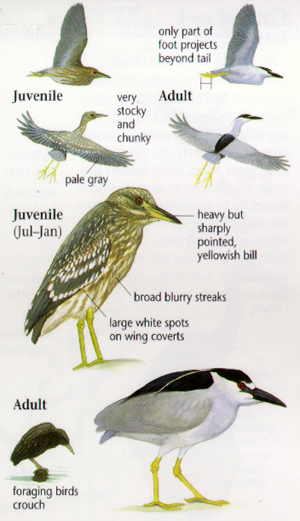

Could it be that our winter resident juvenile Black-crowned Night Heron is surviving by ice fishing??

I was concerned and did not not think the young heron could possibly find enough food after Niles Pond froze solidly over. The pond was thick with a heavy layer of ice, so thick people had been skating.

Several days ago when out for a walk, I heard a krickly sound coming from the reeds along the pond’s edge. A beautiful Red Squirrel ran across my path. A few moments later, the same krickly krickly sound, only this time when I peered in, there was the juvenile BCNH, sleepy-eyed and shifting on the cold ice.

Off he flew into the trees to warm in the sun.

I walked out onto the ice adjacent to where he had been standing and there, very clearly, was a trail of his perfectly delineated tracks. Not only that, but there was a hole in the ice, surrounded by several sets of his tracks. Having observed BCNH during the summer months standing stock still in one place for hours on end, I can just imagine that he must have stood over that hole for hours waiting for his dinner to swim by. Simply amazed!

If you are having difficulty viewing the photos large, double click and you should be able to see full size.

My camera lens was too long to get a close up of the tracks. I was only able to take these cell phone pics, but you can still see very clearly the heron’s tracks in the snowy ice, and the ice hole.

Cape Ann is located at the tippy northern end of their year round Atlantic coastal range.